Jazz

After World War II, there was strong demand for jazz musicians to perform in clubs on the American military bases in Okinawa. There were hardly any such local musicians at that time, so jazz musicians were brought in from the Stateside, from the Philippines, or from mainland Japan.

Strict contracts were made on the number of performers, so when they were short of hands, local high school music club students were called up to fill in the places. Such students were called “scarecrows” and literally could do no more than hold their instruments. Unaware of such a matter, the American military would pay the bandmaster the agreed-upon amount for a full band.

Bandmasters at that time were either Filipinos or Yamatunchu (mainland Japanese). The scarecrow’s share passed right by the student and went into the bandmaster’s pocket.

In vexation, the local students started to study jazz vigorously. This became the beginning of Okinawan Jazz.

There were about 50 U.S. military clubs at that time. Particularly at some of the officers’ clubs, top-ranking jazzmen from the U.S. or elsewhere sometimes gave performances, just like first-class clubs in New York or suchlike.

In an environment where they could experience high-standard techniques firsthand, and given the fact that good play guaranteed good pay, local high school and university students worked hard to improve their skills. After a few years, those scarecrows reached a level of competence that enabled them to play to the highest standard with only the local musicians. The power of the dollar is terrific.

Okinawan jazz flourished under American military administration. At one time, there were about 800 players and 50 vocalists actively engaged in jazz on this small island of Okinawa. Although the island had been devastated by that loathsome war, Okinawans have since olden times been great lovers of uta-sanshin1, and it was this Okinawan inclination for having a good time that made the music bloom again in this form of jazz.

However, other than the American military personnel, there were only a few privileged Okinawans with the opportunity to listen to such music. As for ordinary Okinawans who had become fond of jazz through hearing the music over radios2, they would go to the military base gate to pester the guard with nonsense, until eventually the guard would allow them to slip into the club. Of course, they only had to go in the club from the back door. Closer to the back doors were kind-hearted Okinawan cooks and waitresses, who would let them in without a problem.

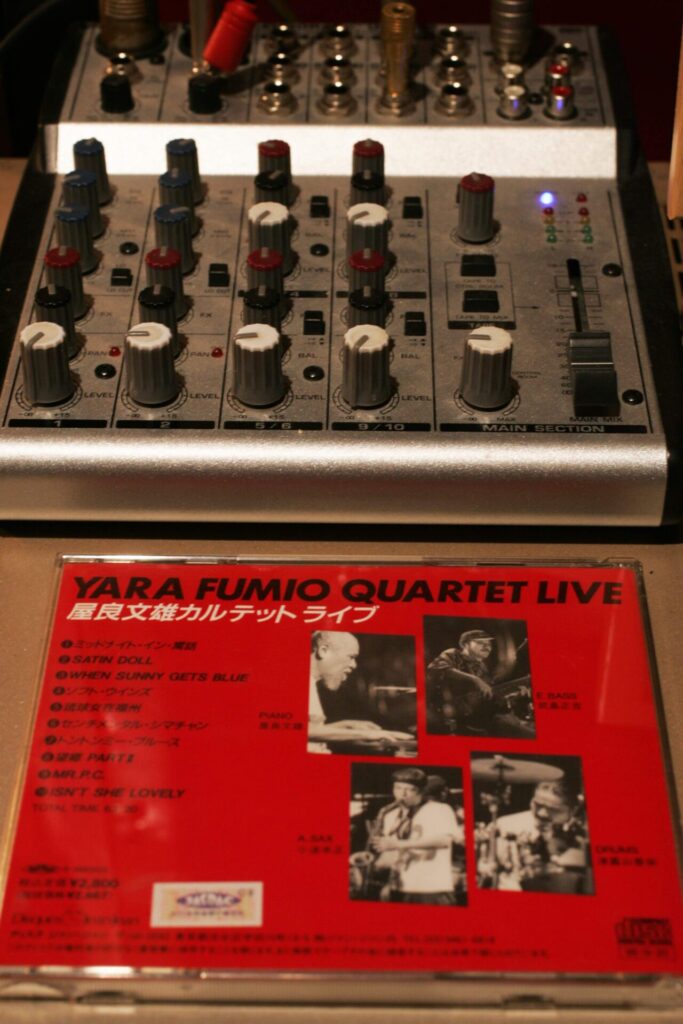

The exhaustion of the U.S. in the foolish Vietnam War, and the Japanese government who didn’t appreciate the allure of jazz ultimately led to the closing of many clubs and the unemployment of jazzmen. Some musicians went to the States and prospered but most withdrew from their activities, thrown out in a world apart. Okinawan Jazz faced a crisis at that time. To play is a fool and to listen is a fool; however, under such backbiting, musicians who could not give up on jazz kept playing over many years of hardships. And now, there are as many performances based on clubs with live music as in New York. Okinawan jazz is going strong!

Editor’s Note:

- Songs played with sanshin, the traditional three-stringed banjo.

- Oyako-radio – a communal radio reception system, settled in 1952 with the aid fund of the U.S. military. Since radio receivers were costing and the radio waves were weak at that time, it recorded 120,000 subscriptions by 1958.