ONNA Nabe and YOSHIYA Chiru

Photo: TARUMI Kengo

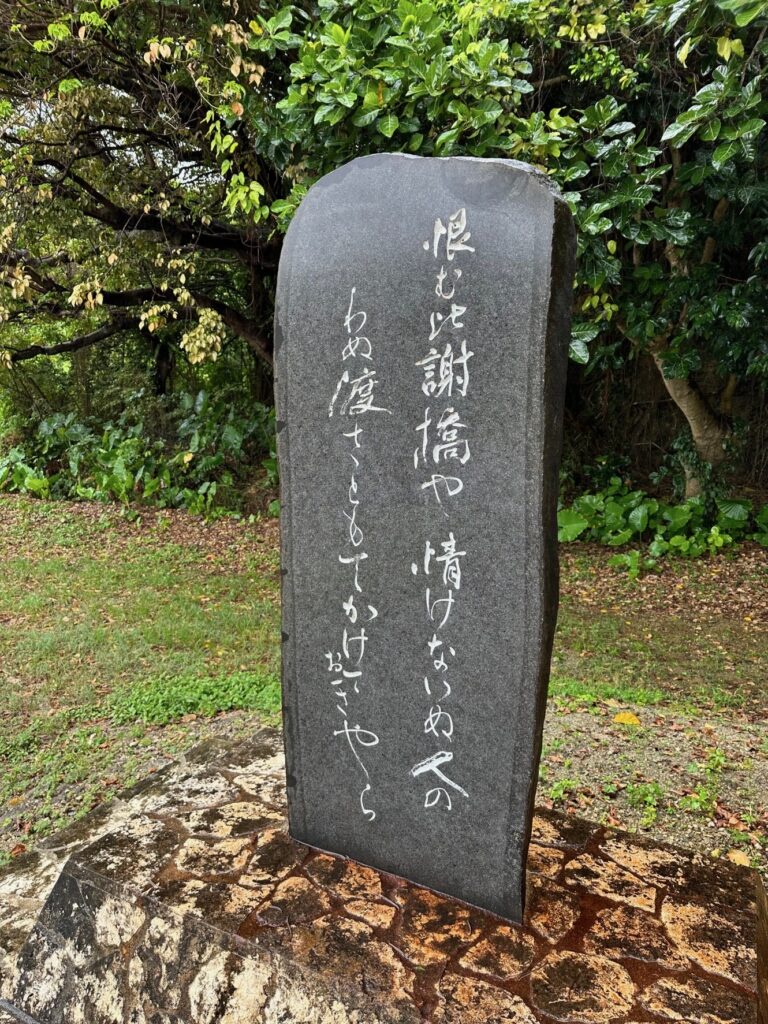

Th passing of the bridge implies herself being sold; the resentment towards the one who built the Hija bridge on the road to Naha conveys a sense of sorrow.

Photo: TARUMI Kengo

They are said to be the two greatest female poets of modern Ryukyu and the two authors representing ryūka, Okinawan poetry, with totally different poetic styles of equal greatness. We must take a roundabout way of stating “they are said to be” for their proof of existence, and—from a certain point of view—the evidence of them being ryūka poets are lacking, given that some theories describe Yoshiya as a singer, and Onna as an editor.

At the start of the 20th century, there was a controversial debate on whether Minamoto no Tametomo1 had visited the Ryukyu Kingdom or not. At that time, Iha Fuyu2 claimed that although we have no material to deny the statement, we have the materials to affirm it. I remember being impressed by this comment. I would like to stand here as Iha did. Poems that are said to be their work still remain today, so they did exist, and they must have been the writers of the poems.

According to ryūka researchers, Onna Nabe’s year of birth and death are unknown, though considered to be around 1726. Not everything is evident on the birth and death year of Yoshiya Chiru too, but the Koke no Shita3 by Heshikiya Chobin states that she was born in 1650 and passed away in 1668. Then usually it must be “Yoshiya Chiru and Onna Nabe,” yet it is the opposite. I believe this comes from the tone of their works.

A. Uyubaranu twu miba Umui masu kagami Kajiya chon utsuchi

Ugami bushanu

A love of forlorn grows the affection stronger

At least a glimpse of him I wish to see in this mirror

B.Unnadaki agata Satwuga umari jima Muin ushinukiti Kugata nasana

Beyond the mount Onna is my lover’s village

I hope to push away this hindering mountain

and draw the village of my lover to my side

The poem A by Yoshiya suffers in smoldering agony, while the poem B by Onna is full of vigor that tries to move even a mountain. There is a clear difference in the figure of these works. If we were to classify them in our familiar way, Manyō-like4—a constellation of poems from peasants to the emperor—or Kokin-like—a selection of works edited by the nobility—then the leading theory is unquestionable: the works of Chiru are Kokin-like in rhetorical and technical aspects, and those of Onna are Manyō-like given the encompassed tolerance. If we were to arrange them like in the textbooks, then naturally B would come before A.

That is strange. Why is the precursor Yoshiya Kokin-like (published around 905) and the aftercomer Onna Manyō-like (published around 780)? Quite interestingly, their works have totally reversed the history of literature. To reveal the trick, this fact owes to the place they lived.

Yoshiya was a courtesan, and the licensed quarters were a kind of salon. From the fact that her lover was said to be an aji, a nobility, who belonged to the intellectuals and practiced poetry, we can presume that Yoshiya was able to learn the poetry of those days before anyone else. Onna was a farmer. She lived in the mountains. The spread of culture inverted the chronology of their works.

Since when did these two ladies come into the spotlight? I could not find any material regarding this question, but an essay was written in 1908 pointing out the resemblance in the words of Victor Hugo and the poems of Yoshiya (“A Passage from a Sickbed Diary” by Iha Fuyu), and another was written in 1911 discussing the ideology of Ralph Waldo Emerson with the works of Onna (“Upon Onna Nabe” by Sueyoshi Ankyo). We can suspect that the rage for these two female poets started to rise around this period.

Editor’s Note:

- Minamoto no Tametomo was a samurai of 12th-century Japan.

- Iha Fuyu is a Okinawan scholar of the 20th century.

- Under the Moss, written around 1725.

- Manyō-shu and Kokin-shu are both classical anthologies of Japanese poems. While the Manyō-shu (around 780) is a collection of poems written by peasants to the emperor, Kokin-shu (around 905) was a selection of works conceived under the order of the emperor.